Laughter fills the halls of the Peterborough Public Library on a chilly February morning, as children and their families gather around to hear a local drag queen, Betty Baker, read stories about friendship. Brightly dressed in an orange wig and a colourful dress she made herself, Baker and friends guide the audience through a series of stories and songs over the 30-minute “Drag Queen Storytime.”

While children joyfully sing along to You’ve Got a Friend in Me, a police officer anxiously checks in every few minutes — a reminder of what’s happening outside.

Security and police flank the library entrance as supporters of the event — armed with squeaky toys and bubble wands — prepare to drown out the protesters expected to show up. And show up they did.

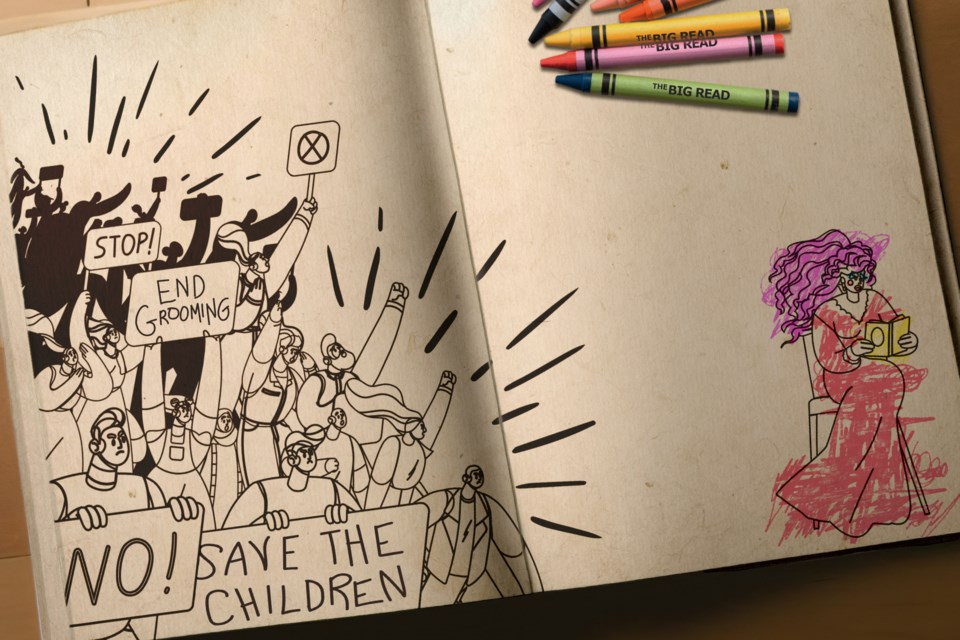

As young as 11, some of the protesters station themselves across the street from the library, waving signs that proclaim “Save Canada, End Grooming, Drag is not Child Friendly” and “Jesus is King.” Others — like the group of teenagers sporting camouflage clothing, cowboy boots and MAGA-style hats — dive into the thick of it, ready to argue that the event is inappropriate and goes against their Christian beliefs because a drag queen is involved.

One protester defends the group's actions, claiming they are “protesting a pervert reading to kids.” Says Josh Alexander, one of the protest leaders: “Watching children be exposed to a sexual thing, I’m not going to stand behind that."

Barbs, insults and bible verses are exchanged. A few fists are nearly thrown. All the while, the children inside carry on laughing, singing and having fun, completely oblivious to what is happening a short distance away.

Although it may seem bizarre for a public library to require ramped-up security for a children’s event, scenes like this have become all too familiar. Fuelled by conspiracy theories and emboldened by a growing far-right movement festering online, protests against family friendly drag events have been erupting in cities across Ontario, and the country, for months.

They’ve appeared in big cities like Hamilton and Ottawa, northern communities such as Sault Ste. Marie, and even small-town Midland and Elora. And it’s not just angry talk. The Brockville Public Library held a storytime event in December that was met with an arson attempt and bomb threat. The protests have escalated to the point that Ontario’s NDP recently put forward a private member’s bill in an effort to help keep LGBTQ+ community members safe at public events.

In many cases, the protesters screaming outside public libraries are the same far-right groups that fought loudly against vaccine mandates during the so-called “Freedom Convoy.” But now that mandates have been lifted, they have seemingly turned their attention to drag storytime events — convinced that the performers are dangerous pedophiles trying to groom children.

But the escalating anger really isn’t about drag, or just about drag. It’s part of a broader attack on the rights of the queer community — and the idea, however false, that those rights somehow pose a threat to kids and the family unit.

“We had about a decade of gay rights and especially rights for queer and trans youth which is something that historically hasn’t really been addressed,” says Cameron Crookston, a University of British Columbia lecturer who has been studying drag culture for close to a decade. “It’s more about the idea that if gay people get more rights that’s somehow going to hurt children or hurt the family unit. This is the same argument, but the target has slightly shifted now because drag is really popular, really visible.”

Drag can be traced back thousands of years to men playing the roles of women in theatre, but according to Crookston, modern drag has its roots in the mid-to-late 19th century, when underground queer subcultures and communities began to form. “Most distinct cultures have distinct art forms,” he says. “And because queer people were so policed that it was so difficult to have any above-ground, legal, public facing representation, drag filled that need.”

Early modern drag performances took place wherever they could, from truck beds at PRIDE events to bars, nightclubs and event spaces. But that changed in 2009 with the arrival of RuPaul’s Drag Race, a hugely popular reality TV show that features drag performers competing in challenges. It has since seen multiple spin-offs, propelling drag to the mainstream on a level never seen before — so much so that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made a brief appearance on the Canadian version last year.

And in 2015, drag became more family friendly, with storytime events popping up all over North America. In Canada, they were started in Kingston by Matt Salton, the executive director of the queer film and video festival Reelout.

Salton has been running drag storytimes for eight years and never saw any backlash or protests until recently. Sadly, he was not surprised. “This idea that homosexuality and pedophilia are one in the same, I’ve heard this all my life growing up,” he says.

Protests like the one in Peterborough have flared up across Ontario at libraries, shops, family friendly restaurants, and various Winter Pride events since the summer. Betty Baker was forced to cancel a reading at a local store after the owners received threats. It was scheduled for the same day the Brockville Public Library held its storytime event, which triggered an arson attempt and bomb threat.

Baker, 19, started performing drag when she was 15 and was more recently encouraged by her mom Michelle Fenn to start doing drag storytime. None of her performances were met with any hate until last September. “I’ve never had anything like this happen to me before,” Baker says. “It definitely scares me.”

She says “drag is such a multi-faceted art form, whatever you want it to be. So to pigeonhole drag as something that is inherently sexual, it’s not true.”

For people like Baker, this type of hate is completely foreign. But for Tyffanie Morgan, who has been performing for more than two decades, it feels like history is repeating itself.

Growing up in the 1990s in northern Ontario, she remembers hearing “the local bigots talking about the gay store clerk, how they wouldn’t let him touch them. They would insist spare change to be placed on the counter so they wouldn’t make physical contact, and would send their children to a different store to avoid being preyed upon.”

When she came to Kingston and started performing drag in 2000, things weren’t much better. She wouldn’t walk to the venue or take public transit because the risk was too high. Instead, she would take a cab and get ready in the bathroom at the bar. And once inside, she would always do a risk assessment.

But after drag became more mainstream, things started to look a little different. “There was a period when it really looked like everything was moving in a different direction in North America,” says Jennifer Saul, a professor at the University of Waterloo who specializes in the philosophy of hateful language.

Things felt so much safer, in fact, that Morgan actually walked to a venue — in full drag — about a year ago. “It made me realize how comfortable I had become,” she says.

This was the world Baker was familiar with: one where she didn’t need to worry about her safety as a drag queen. But that pocket of safety has burst, she says. “My comfort has been shaken by protests at drag storytimes,” Morgan says. “I’m checking for fire exits and back doors. I’m ensuring someone walks with me from the car to the door of the venue.”

For Baker, Morgan and many others, the shift seems to have come out of nowhere. But it’s been brewing for a long time, Saul says, making it hard to pinpoint the exact moment it began.

Some point to the 2022 Club Q shooting in Colorado, where five people were shot and killed at a queer nightclub. But Saul says the rhetoric was already ramping up when that shooting happened, and might even bear some of the blame for it. According to a study released by Montclair State University, the usage of terms like “grooming” and “groomer” experienced a huge spike in the days following the massacre.

By definition, a groomer is someone who sexually abuses children after gaining their trust. “But it’s been appropriated by people who want to push anti-trans conspiracy theories about trans people trying to sexualize children and do something bad to them,” Saul says.

Although she says that approach is new, it resembles earlier homophobic rhetoric about gay people trying to recruit children. Peter Votsch, a retired union rep, longtime outreach worker and one of the organizers of the counter-protest in Peterborough, agrees.

“In the 70s, when I was cutting my teeth politically, there was a call by the far right to remove gay male teachers from schools, for the same thing that they’re accusing Betty Baker of,” he says. “We’re always accused as gay people of grooming children. We can’t be teaching them, we can’t be telling them stories. We’re always grooming.”

Though the conspiracy of queer people being groomers and pedophiles has surfaced up time and time again, this recent resurgence of the rhetoric is tied to far right QAnon conspiracy theories originating from the U.S. “There’s this slight change of vocabulary, but really it’s very much the same kind of theory being pushed,” Saul says. “The other main difference is that it’s now part of this very broad, very strange wave of really wacky conspiracy theories going on right now.”

In particular, it stems from a QAnon-induced moral panic that children need to be saved, largely from the sinful, satanic left. Not all conspiracies are dangerous, Saul says, but these ones are. “These theories are not only incredibly weird and counterintuitive, and require a whole lot of ignoring of facts,” she says. “But they’re also incredibly dangerous and are motivating people to violence.”

In the U.S., where Saul and others believe the rhetoric originates, some politicians and prominent media figures are perpetuating the ideology. “What's going on is really scary,” she says. “And there are a lot of acts of violence being committed in the name of these theories.”

Although the far right’s focus on drag and trans rights is relatively recent, Saul says the broader phenomenon of growing far-right conspiracy theories has been a long time coming. And once you believe one wild conspiracy, you’ve opened the doors to pretty much all others. “You have people who started out just wondering about the moon now thinking drag queens are pedophiles,” she says.

One of the main players in the anti-drag movement is Nico King. “Sodomites!” he can be heard yelling in a YouTube video, as he is cuffed and led away while protesting earlier this year at a drag storytime in Ottawa.

King is on a self-proclaimed crusade to recover society from the satanic left who have turned the world into what he believes is the equivalent of Sodom and Gomorrah. In an interview, he says he was arrested for reciting biblical verses referencing “Babylon and Sodomite abomination.”

For the last six or seven months, King has teamed up with fellow “crusaders” like Chrystal Peters to protest drag events across the province in what has essentially become a full-time job. King didn’t begin protesting with drag events, but said he was involved with noted anti-lockdown and anti-vaccination figure Chris Sky fighting COVID pandemic measures.

His main concern is children being targeted with “sexually charged drag shows” at all-ages events and being read material that pushes children to be transgender, non-binary or drag queens. “The government we currently have is making a big push for it and we know that the Trudeau government is funding it,” King says, making sure to point out Trudeau’s cameo on Drag Race.

What would be gained from this, King explains, is to weaken society to create a new world order of 15-minute cities, vaccine passports, digital IDs and digital currency. He says he is aware these kinds of statements are considered conspiracy theories by a vast majority of people, but he believes these views are catching on.

Another major player in the protests, the "Save Canada Army," was born out of a similar desire to promote “free Christian values” and to combat the continued “attack” on their way of life. The Trump-inspired, youth-run volunteer organization was also present during the Freedom Convoy, but recently turned its attention to drag storytime events, claiming it is inappropriate for a drag queen to be around children.

The face of that army in Ontario is 17-year-old Joshua Alexander from Renfrew County, on the west bank of the Ottawa River. At the protest in Peterborough, Alexander was with a few other people who appeared around his age, sporting red MAGA-style hats that read “Save Canada,” and getting into arguments with counter protesters.

He became something of a recent icon in certain circles for being vocal against transgender students at his high school using their preferred bathroom. Alexander says he was arrested. “We decided we had a good opportunity to stand up for what we believe in and voice our opinions on the over-sexualization of children in our culture,” he says, standing outside the Peterborough storytime event.

Facing a sea of counter-protesters, Alexander does not back down from his opinions. “It’s not going to faze me,” he says. “I mean, there’s a lot of evil in our world but all we can do is stand up for what we believe in.”

The night before, the group stayed at the home of Maggie Braun, who said she was arrested at gunpoint in Ottawa during the Freedom Convoy rallies. She also testified during the Emergencies Act hearings in late-2022. Braun says she met the Save Canada Army at previous protests and considers herself more of a civil rights activist.

Hazel Woodrow, education facilitator with the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, says a lot of the people protesting drag shows and the broader queer and trans community are the same people who organized against lockdowns and mask mandates. Braun chalks it up to a simple case of opposing political views.

“Maybe because it seems like it’s a leftist thing to be like in support of lockdowns and masks and everything and it’s a leftist thing to do this,” Braun says.

It goes back further than that, though. “I think it is part of a rise in far-right populism that we have seen growing and really thriving throughout the pandemic and even before that,” Woodrow says.

But when lockdowns, vaccine and mask mandates were lifted, fired-up protesters had to turn their energy somewhere. They landed their collective gaze on family friendly drag events. “Vaccine mandates and COVID kind of galvanized people on the right so that they have a lot more organization and they’re more radicalized, so they’re doing a lot with that energy and that includes attitudes towards drag and queer people,” Crookston says.

But how are far-right conspiracies like these seemingly reaching so many people and inciting sometimes violent action? Social media is partly to blame, making it easier than ever for conspiracy theorists to find each other and share their ideas. But the type of language being used is also to blame, according to Saul.

“Figleaves” are phrases people use to make hateful statements more digestible to the average person. Saul offers an example: I’ve got nothing against trans people, I just don’t want them near my children. “That allows people to feel more comfortable with the messages, and more comfortable sharing [them],” she says. “And I think that move is one that really helps these wacky conspiracy theories to spread.”

If a person is on the fence and comes across a statement like that, they may be more inclined to believe the theory or share it on social media “because you want to know what other people think.” But using that type of language can be very dangerous, Saul says. The more they’re shared on social media, the more people they reach.

It also makes people “feel more comfortable sticking with politicians who are actually spreading wild conspiracy theories. And [these] aren’t innocent ones. These are conspiracy theories that are making people go out and attack people. And that's incredibly dangerous.”

Although many of the people spreading this rhetoric claim they aren’t transphobic or homophobic — they just want to “save the children” — Florence Ashley isn’t convinced. “It’s certainly not about protecting the children in a genuine sense,” says Ashley, a trans activist and doctoral candidate at the University of Toronto.

Instead, Ashley says the backlash is all about protecting children from deviating perspectives that go against the conservative norm. “People are really trying to justify their transphobia,” they say. “This is really just an excuse, in this regard, saying: ‘I’m not transphobic because it’s about the kids.’ Well, the kids have always been used as the justification — that’s not anything new at all.”

The intent doesn’t matter, Ashley says. It’s the impact that counts: the spreading of dangerous anti-trans rhetoric.

“They really feel like they’re doing something that’s for children,” Salton says. “They really do, and it’s terrifying.”

It has been difficult for performers like Baker to continue. “Nobody wants to receive death threats online, or to have protests against them,” says the Peterborough drag queen. “It doesn’t exactly do good things for the psyche…Having people in Facebook conversations [say] you’re literally a groomer and a pedophile, it makes you scared, because I’m not, but there’s no way for me to prove that.”

Despite all the anger and negativity, Baker has no intention of stopping. As someone who grew up queer, she knows how important these events are. “To have role models to look up to is important. I don’t know if I’m a role model but I would like to be, and I would like to be a part of my community in a way that is positive, in a way that enacts positive change.”

Camilla Elston, a parent at the Feb. 25 storytime, regularly attends the events with her children. “We’re a queer family, so it feels really important to go to storytimes that are inclusive and diverse and we know that we’re accepted,” she says.

Amber Sherman was there with her mom and five-year-old Lennon. They “absolutely loved” their first-ever drag storytime in September and were shocked and confused by the protests outside. So in February, they came out as counter-protesters, with signs showing support for Baker.

“I think it’s really important to come out here and talk to people and tell them what actually is happening inside the library — a great literacy experience for children,” Sherman says. “They sing songs, each storytime has a theme like emotions or friendship, so it’s all about something valuable to teach the children.”

In the end, the Peterborough protesters accomplished next to nothing. Many in the crowd simply ignored the teenagers calling themselves the Save Canada Army, and although there were some tense moments — and near fights — nothing boiled over.

“You have to oppose fascism in the streets, you have to show up whenever they gather and tell them they’re not welcome,” says counter-protester Galen Crampsey. “Gotta be as peaceful as you can, but fascists are known to be violent and, you know, whatever transpires you meet them where they stand.”

Will these protests continue to spread? Will drag storytimes continue to be a flashpoint for the far-right? Could it lead to more violence? Or worse, legislation that negatively impacts trans people?

And when it comes to all the hateful rhetoric — drag queens are groomers and pedophiles — what can be done to counter it?

Hate speech is a bit of a grey area, says human rights lawyer Marcus McCann. Although saying that a certain group is a threat to children has all the hallmarks of hate speech, McCann isn’t aware of a specific case involving the term “groomer.”

However, there are measures that can be taken on social media to help identify and prevent the spread of misinformation. It can be done in various ways, Saul says, including through ads that encourage people to question the validity of the information they’re reading. “There is evidence that these things make a difference,” she says. “But of course, if you look around at the world, it clearly hasn’t fixed things.”

Because social media is such a new technology, she says society hasn’t yet figured out how to “cope with the massive potential it has to spread hatred and misinformation.” Which is why she says education and awareness are so important, providing people the tools they need to notice tactics used to spread misinformation.

Morgan, the veteran drag queen, would like to see something else: for authorities to investigate key stakeholders, and for politicians to step up and condemn the people spreading this rhetoric and showing up to protest the events. (Some politicians already are. Earlier this month, the Ontario NDP proposed a private member’s bill that would allow the attorney general to designate safety zones for queer community members at specific locations for a certain time period.)

Although some events have been cancelled due to safety concerns, many venues, libraries and performers aren’t backing down. They plan to continue with storytime events because of the important role they play in reflecting diversity and fostering acceptance.

Says Morgan: “Sweet Pea, you can’t put me back in the drag closet. Drag is here to stay.”

Keegan Kozolanka is a general assignment reporter for EloraFergusToday, which he helped launch in 2021. He has worked at Village Media for three years.

Taylor Pace has been a reporter at GuelphToday since June 2022. She is a graduate of the print journalism program at Conestoga College, where she won several awards for her work.