SUDBURY — His presentation started with a disclaimer that his views may not represent those of Vale Canada Limited, even joking he may not work for them after what he had to say about zero harm policies in the mining industry.

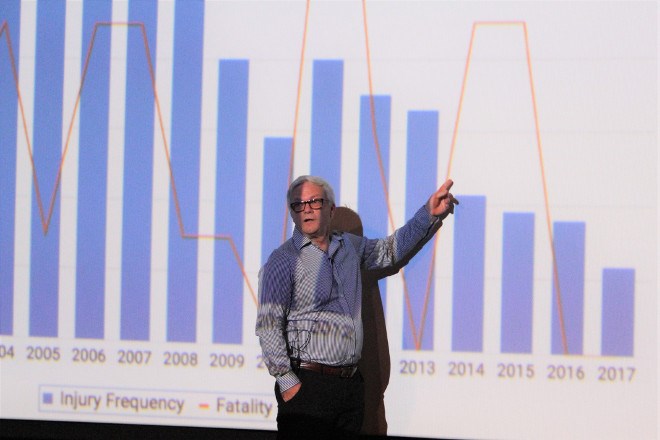

Alistair Ross, director of mining, Ontario Operations, delivered a comprehensive presentation at the first general membership meeting of 2017 of the Canadian Institute of Mining on Sept. 21 to a packed house at Dynamic Earth in Sudbury.

It focused on the policies that are meant to eliminate injuries and deaths in mining workplaces actually end up becoming harmful policies by adding too much structure and setting impossible goals.

His message sent gasps around the room. As long as humans are not factored into mine planning, injuries and fatalities will happen. Humans work in in the mining industry, humans are a collection of mistakes, humans need to be taught what it means to be human before we can start to solve problems.

“Look at who we appoint to the managerial positions, the best engineers,” he said. “I wasn't taught by humans, only engineers, I lived my life like an engineer. The whole point of being the best engineer I could be was if I had no humans in my plant. When you train up engineers like we do in Canada, it's actually tough to make a transition.”

The only way to make a transition and tackle the problem of workplace injuries and fatalities is to stop identifying themselves as labels and remember they are humans.

Whenever a proposition goes wrong, he said people need to start their inquiries back at the fact they are humans who make mistakes.

This problem goes all the way back to basic education, he said. The curriculum never teaches people what it means to be human.

“We are teaching managerial leaders, and who are you leading?” he said. “You are not leading machines, you don't lead systems. It's people. And the people we are putting in charge of people know nothing about people.”

Behavioral economics are not being considered when setting policies. Humans are complex social creatures, he said. Once society teaches people what it means to be human it starts the process of achieving zero fatalities. Right now putting the goal of zero injuries on foremen going down into the mine is impossible. They should be rewarded and praised for their good jobs rather than piling on mind-numbing statistics.

To point that out, Ross said he's dealt with 1,700 incidents this year alone.

He pointed out the nine common killers in mines: blasting, open holes, rock bursts, mobile equipment, run of muck, compressed air lines, electrical, ventilation, and fire. The way to reduce injuries and fatalities is to either design them out or reduce the number of times humans have to interact with them.

“At the design phase, we should reward engineers for showing a calculated reduced probability of fatality because the number of times a person became associated with one of those killers,” he said.

Ross related the history of safety at Vale, going back to the Inco days in the 1980s, when their safety record was so bad they reached out to DuPont, a company with one of the best safety records in North America. When officials came in they laid the blame for their high frequency of death and injury in Sudbury on the very safety policies that were meant to stop it.

“They came in and basically said, it's so heavily proceduralized and and systemized, no wonder you guys can't be safe,” he said. “It's hard to do business here. Get back to simplified.”

DuPont eliminated the probabilities involving kill risks, specifically with explosives. The stopped manufacturing explosives 40 years ago due to the high risk it could harm or kill humans in their plants.

This meeting comes on the heels of two major shakeups, the closure of Stobie Mine and the suspension of the crushing plant at Clarabelle Mill.

While Ross said he couldn't comment on the current economic situation at Vale, Angie Robson, manager of corporate affairs, said it has been a tough few months for the company, stating those were difficult decisions.

“It's been bad not just for Sudbury, for the whole industry,” she said. “The price of nickel has been prolonged for a very long time. We had to make some tough decisions.”

The closure of Stobie Mine meant there would be what she called “employee surplus."

To ensure no Vale employees were laid off they replaced embedded contractors with Vale workers and offered retirement incentives to others.

“We operate on the principle of mitigating impacts as best we can,” she said.

When asked about layoffs, she said no decisions have been made.

On the presentation, she said it was great to have Ross talk about safety, praising his long career with Vale and his passion for safety.

“At the end of the day, he just want to make sure everyone gets home safely.”

— Northern Ontario Business