It all began with a small and rather unimpressive bang, accompanied by the tiniest puff of smoke, which seemed almost to be apologizing to those in attendance for its lack of grandeur in the face of the importance of this event.

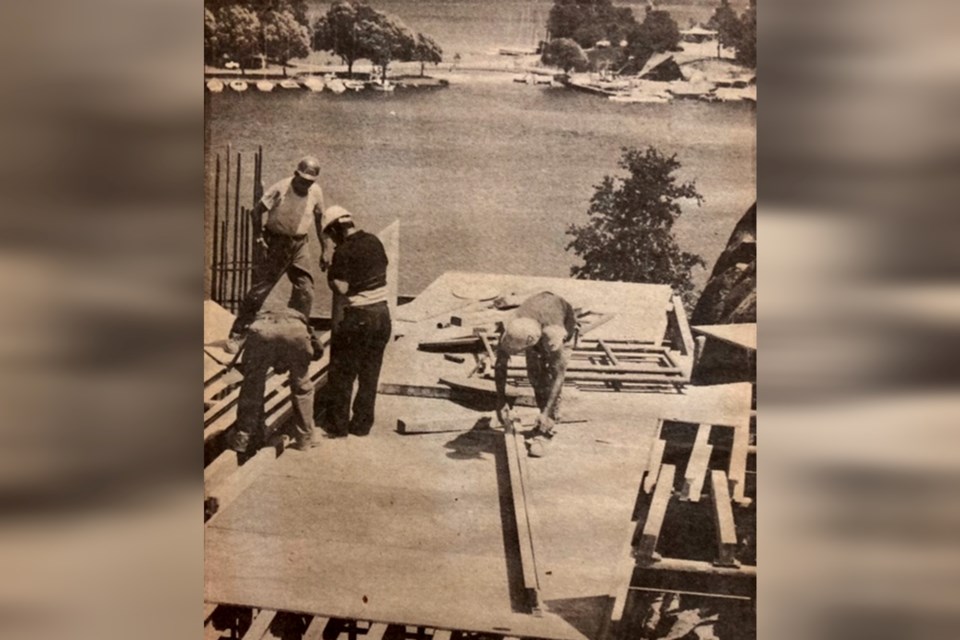

Even the gloomy weather that day was far from projecting a jubilant atmosphere. In all honesty though, even a small scale blast to officially launch such an important construction project, in this capital of Canadian mining, is a much more fitting choice than watching politicians with shovels for the more traditional groundbreaking photo-op.

Nonetheless, this was an occasion of real historical significance for Sudbury. On this Thursday morning in late June, 1981, beside a rocky outcropping at Bell Grove, a project tentatively named the Sudbury Science Centre first began to take steps toward becoming a reality for its creators.

But, where (and when) did the genesis of such an important project in Sudbury’s history and such an impressive addition to our landscape first take shape? Looking into the origins of the project, George Lund said at the time that the first suggestion for a science centre appears to have been made in a column in The Sudbury Star around 1965.

However, the first serious push for the project came from the late John McCreedy, vice-president of Inco Ltd. This led to support from former Inco chairman J. Carter and a subsequent report by Dr. J. Tuzo Wilson, head of the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto, who found "Sudbury, by its nature, is one of the most suitable places in Ontario to start such an enterprise."

By 1978, politicians and educators in Sudbury were going all in on proposing that a new Science Centre should be established in Sudbury. They believed (as Dr. Wilson had stated) that Sudbury was “a natural location, a place where the earth's geology had baffled geologists, where advances in technology allowed the drawing out of our natural resources, and where science was helping a once-bleak landscape to become healthy again as researchers pioneer regreening studies.”

In mid-1980, even though at that point no one quite knew what the proposed Science Centre would look like, where the money to fund it would come from, who would ever visit it and what exhibits were to be included, the planning committee’s spirits were high and their imaginations were working overtime.

As the appointed project director, Dr. David Pearson told reporters at a press conference in 1980, that he would drop the lawnmower on a Sunday afternoon and dash madly to the typewriter when inspiration struck.

The Sudbury Science Centre that Pearson had in mind was to be a "people place" like no other in existence, a "world-class" showpiece. Among those he expected to participate in its programs would be retired miners, craftsmen, artists — in fact, just about everyone with some sort of expertise to demonstrate and educate the masses.

From the beginning, its design was planned to be “participatory.” Children would be able find plenty of buttons to push and wheels to turn and so on (certainly not your grandparents museum of dusty, static exhibits).

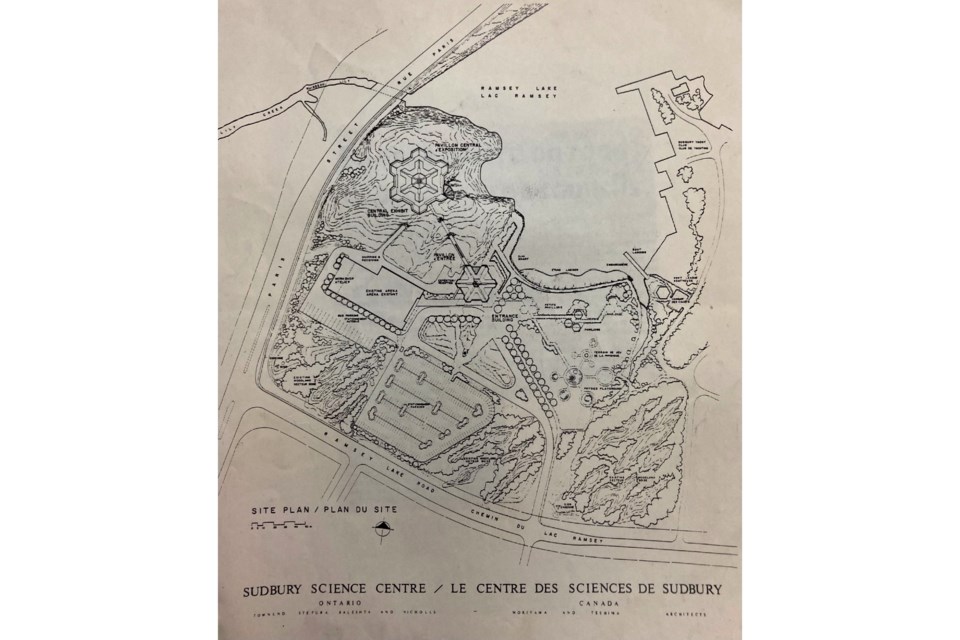

At this point, the Science Centre’s study team (Inco contributed $150,000 for the study) appeared before the City and Regional Councils seeking an approval, in principle, for locating the project at Bell Grove, on the western end of Ramsey Lake. The team called it a "magnificent setting."

Both councils gave the project location their unanimous blessing. The projected opening of the Centre was also announced as being in 1983 in order to coincide with Sudbury's centennial year.

The Bell Grove site was approximately 75 acres in size, with the proposed building expected to occupy about two acres of it. Discussions were then required to decide if the property would be bought or leased from the city.

Bell Grove was chosen as the optimal site after considering a total of 44 locations throughout the region, including areas in Walden, Gore Lake and a site halfway to Coniston. Suggestions were submitted by real estate agents, the regional planning department, Nickel Basin Properties Limited (Inco), the municipalities of Walden, Onaping and Valley East, private individuals, members of the study team and staff members of the Sudbury Regional Development Corporation. Some sites were even revisited as many as five times.

Marketing consultant Jack Ellis said at the time that three major criteria were kept in mind during the site selection process: tourists must have convenient access; residents must have convenient access, and most importantly; the location should represent the best features of the North.

A survey of the region's highway corridors indicated that the largest volume of traffic was on Highway 17 West/69 South, much of which used the southwest bypass.

It was decided that any site for the centre should be within five to eight minutes driving time from the bypass. Area residents should also be able to reach the site within a five-minute drive from the Elm/Paris Streets intersection or on a bus route with a high level of service.

The data concluded that the best location for tourists would be on the southwest bypass, while the most accessible for regional residents would be at the corner of Elm Street and Notre Dame Avenue.

Bell Grove, being a midway point between the two, had the advantage of having a "blend of exposed rock, trees, open vistas and a shoreline," said Ellis. He added that “the Paris Street entrance is probably one of the most pleasant of any city in Ontario."

Ellis could not say how many tourists the centre would attract, but he estimated that “if 100 tourists per day stayed overnight, $2.3 million per year would be generated in the community. Other benefits would include 50 jobs for each 100 tourists, a boost to the retail, accommodation, food and beverage, recreation and amusement businesses and perhaps the most important and long lasting effect, an enhanced image of the area.”

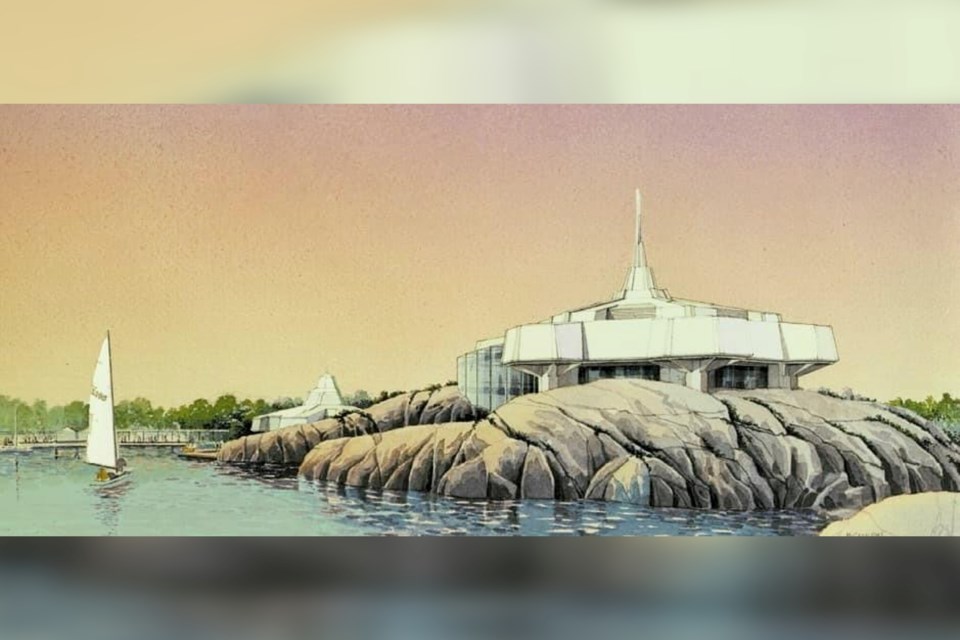

Now that a site had been determined, Toronto architect Raymond Moriyama (of Moriyama and Teshima, the firm who designed the Ontario Science Centre) and Sudbury architect John Stefura, took on the task of realizing what, up to that point, had been only a vague concept. Moriyama admitted at the time that he "started the project with a great deal of cynicism," referring to Sudbury's negative image in southern Ontario, but said that he'd like to take Sudbury's proposed centre one step further than the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto. As he started putting his ideas onto the drafting board, he said that he did not have a fixed image in his mind yet of how the Science Centre would look, preferring "to keep my mind as open as possible,” but he spoke of “a world-class attraction that would have enough intrigue”for all curious parties.

By the middle of January 1981, the physical concept of the Sudbury Science Centre had finally begun to take shape. What was proposed was a six-sided centre set both inside and above the rocky outcropping at Bell Grove. The public would enter the central building through an underground tunnel from a smaller adjacent building. The project's design also included a wharf and nine science pavilions, along with a physics playground in an outdoor park setting.

The architectural team spoke of basing their plans for the construction of the (initially) $18-million science centre as connecting two images: the early crater of the Sudbury Basin and the snowflake.

“The crater, resembling the open pit, symbolizes the early beginnings of the region and the best mining techniques in the world," said Toronto architect Raymond Moriyama. “The snowflake is the symbol of the glaciation and the climate that shaped the northern land. Thus the synthesis: the snowflake settling gently over a rugged crater."

During the initial stages of construction work, a natural geological exhibit for the centre (and an important part of the crater of the Sudbury Basin) was uncovered. As soil was being removed to uncover the bedrock on which the buildings would sit, a four-metre deep slot, smoothed and polished, was discovered. That slot marks the Creighton Fault, and is only a short section of the more than 200-km long fracture in the earth's crust. The fault remains visible to this day among the exposed rock below an inclined ramp area, a constant reminder of the geological forces which shaped our area.

Unfortunately, by 1982, the progress on the building of the Sudbury Science Centre had slowed due to varying factors, the most significant of which were delays in construction and a tight cash flow.

On Sept. 12 of that year, Science Centre president George Lund announced the exhibit building would not open in the summer of 1983 as originally planned, which would have been in time to celebrate Sudbury’s Centennial. Instead, the building was expected to open to the public some time in early 1984.

Lund said that, unfortunately, construction had been delayed due to extreme cold weather over the previous winter and also due to strikes in the construction industry during the spring and summer of 1982.

The tight cash flow the centre project experienced for the several months leading up to his announcement had slowed down exhibit construction, Lund said (the centre’s building costs would eventually balloon to $27 million). However, “with the recently announced ($5.3 million) contribution of the federal government development is proceeding and no further delays are anticipated," added Lund. Due to the delays "we have to reluctantly accept that we can't achieve an opening next year," he said.

On the question of the total funding for the science centre, after the initial study (which they had paid for), Inco became the first founder of Science North with a $5-million donation to kick off the fundraising. At the time, this was the largest donation ever made by private industry to a community-based project in Canadian history. Falconbridge Ltd. followed with a $1 million contribution.

Government support for the centre came from all levels. Along with the aforementioned donation from the federal government, the Province of Ontario contributed $10 million towards the project; the City of Sudbury, $1 million; and the Regional Municipality of Sudbury, $1 million.

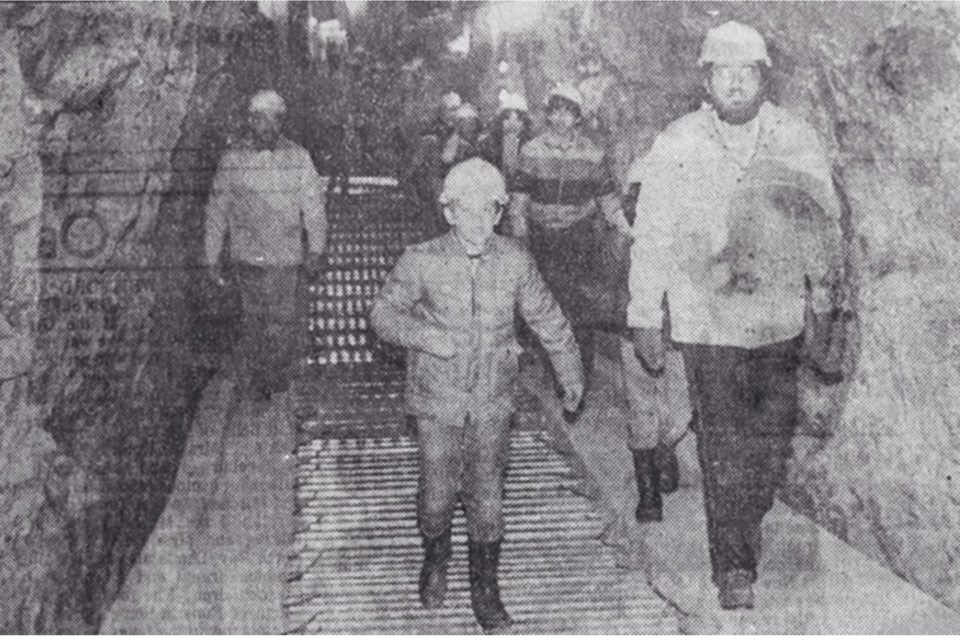

In November 1982, some 1,500 area residents were able to see for themselves a view that only the construction crews had experienced up to this point. In an event called “Tunnel Trek II” they were welcomed into the tunnels of the burgeoning science centre and into the massive rock cavern at its end to view its progress.

The fact that many people turned out to wander around the site on a guided tour bore witness to the large community interest that the project engendered.

During that same week, the science centre board held a reception for community representatives in order to announce that the centre finally had a name and logo of its very own. The Sudbury Science Centre would henceforth be known as Science North and would be identified by a hexagonal-shaped symbol reflecting its snowflake design.

Science North was now much more than a building project, with its shapes and its relationship to its environment; it had become (via its logo) a work of art. (Oh, and there was still another artistic twist to come.)

And, what was that twist you say? In late August, 1983, an 11-metre spire was hoisted atop the Science North building to serve as a lightning rod. But, unique features make this lightning rod an expression of scientific knowledge. A series of horizontal rods spiral up towards the peak, with each bar's length becoming shorter. The graduating pattern and length of the rods is not haphazard in the least. The pattern is based on a law of nature proposed in a number series by scientist Leonardo Fibonacci.

Starting at the peak and moving downward, the length of horizontal rods increases on the basis of an established ratio, the Fibonacci sequence (wherein each number is the sum of the two preceding ones: 1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,etc). The series is considered a mathematical curiosity in itself, but it’s also applicable to nature, particularly plants which develop through “growth spirals”. (For instance, the centre of a daisy or the spirals in pine cone scales).

Science North's spire was also expected to rotate (does it still? Or did it ever? I’ve never noticed) and would be illuminated at night by six spotlights (coincidentally a spinoff of an invention by Thomas Edison, once a visitor to the Sudbury area).

On Sept. 18, 1983, the final pre-opening tunnel trek for visitors to Science North was held to give onlookers the chance to see the completed tunnel and cavern as well as the exhibit floors prior to the anticipated spring 1984 opening.

“Building construction will finish soon, but the installation work will continue through the winter," said Jim Marchbank, the project’s director of development.

Science North staffers anticipated that the exhibit floors would be swarming with activity all throughout the winter to meet their deadline for the following year.

Of course, the Science North board was looking towards its grand opening with a view towards having the most high profile guest possible on hand. So, it was that on Nov. 23, 1983, that Science North organizers, represented by Jim Marchbank, announced that they were "still optimistic" that Queen Elizabeth II would visit Sudbury for the science centre's official opening in 1984.

“I'd be delighted to confirm if the Queen is coming to open Science North," Marchbank said.

At that point, it was announced by Buckingham Palace that the Queen and Prince Philip would be visiting Ontario, Manitoba and New Brunswick in the last two weeks of July.

“The Queen hasn't been to Sudbury since (July) 1959," Marchbank reminded everyone. He then said that he would like to see another July visit for the "official opening which could be set sometime at the Queen's convenience."

Unfortunately, this would (technically) not come to pass. On June 20, 1984, the headline on the front of The Northern Life announced to all: “Science North Now Open!” The centre opened to the public the previous day with an enthusiastic George Lund, chairman of the board of directors for Science North, commenting, "It's the beginning of what we think is a new era in Sudbury.” Queen Elizabeth was unfortunately not in attendance, but was in fact still expected to visit for an “official” opening on July 24.

But, for now, Sudburians and tourists alike were finally able to discover what lay inside the giant snowflake-shaped building in the city's South End. And, still today, in a much different 21st century existence, that nascent dream which became the reality of Science North remains nestled on the rim of an ancient meteorite crater, teaching us about the connections between humanity and the natural world around us.

Happy 40th Birthday, Science North!

Jason Marcon is a writer and history enthusiast in Greater Sudbury. He runs the Coniston Historical Group and the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page. Then & Now is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.