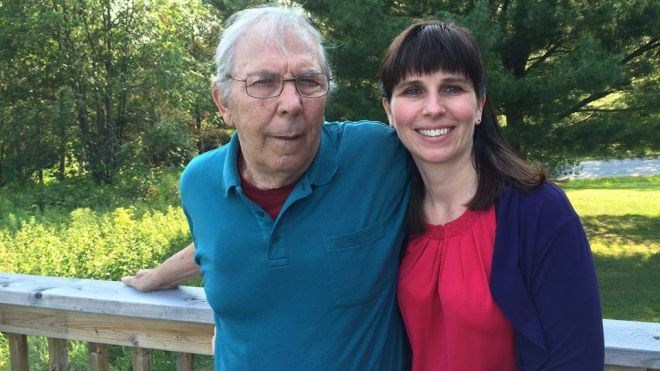

Janice Martell cried when she learned the Ontario Network of Injured Workers Groups (ONIWG) would hold a memorial cycling ride between Massey and Elliot Lake this May in tribute to her late father, Jim Hobbs.

The veteran miner made that same trek countless times between 1978 and 1990 while working for the area’s underground uranium mines. In retirement, Hobbs was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease – something his daughter attributes to his exposure to a finely ground aluminum dust known as McIntyre Powder – which eventually took his life in May 2017.

That ONIWG is recognizing the significance of occupational disease on the province’s workforce while honouring her father and other miners impacted by McIntyre Powder exposure is a gesture that touched Martell deeply.

“They’re going to be travelling the same route that he would have had to drive every day to go to work,” Martell said. “So it was just really very meaningful that they would come to our area and honour our mine workers.”

Established in 1991, ONIWG is a non-profit organization with 22 member groups advocating for workers who have been injured or become ill while on the job. The organization’s annual cycling ride aims to raise awareness surrounding the challenges addressing injured workers, in addition to raising funds for its advocacy work. This is the first time the ride will travel to Northern Ontario.

To greet the riders, Martell is planning a welcoming reception on Friday, May 25 and Saturday, May 26 at the Lester B. Pearson Civic Centre in Elliot Lake.

It will also give her a chance to share with the general public the information she’s learned over the last four years through the McIntyre Powder Project, which she started in 2014.

“I’ve discovered a lot of information from my research and from talking to mine workers and their survivors,” Martell said.

“I’ve been hearing their stories for four years and I’ve been trying to get out as much information as I can, but I really haven’t sat down with these mine workers and said, look, this is what was going on; these are the documents; this is what I found.”

First introduced in 1943, McIntyre Powder was created by mine executives who were looking for a way to reduce worker compensation costs associated with silicosis, a lung disease caused by inhaling silica dust. The theory was that if miners inhaled aluminum first, it would coat the lungs, protecting them from silicosis.

Aluminum was ground into a fine dust and miners were mandated to breathe it in while in the mine drys at the start of every shift. Miners were not asked for their consent or warned of any possible side effects.

The practice – something Martell calls “a big, human experiment” – was later debunked as ineffective and it ceased in 1980. But years later, miners who had been exposed began experiencing a range of health issues, including everything from respiratory illness to neurological disease.

Martell believes McIntyre Powder is the direct cause, but because there is no scientific evidence correlating the dust with the range of illnesses, miners filing compensation claims with the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) have routinely been denied.

Martell believes that’s unacceptable, based on what she says is evidence that the provincial and federal governments of the time were “kowtowing” to industry instead of fulfilling their duties to monitor what the mine executives were doing and hold them accountable.

“If we're saying that as a society we need this gold, we need this uranium in order to function in society, in order to drive our economy, then we also need as a society to say, ‘We are going to take care of these mine workers if they are injured,’” Martell said.

“‘We are going to do everything in our power to ensure that they don't get injured, to control for carcinogens like silica dust, like diesel emissions.’”

In January, she ramped up her efforts, filing a Freedom of Information Act request with the WSIB to release the information about its policy denying claims associated with aluminum exposure and neurological disease. In response, the WSIB quoted the cost of accessing that information at $7967.95, and Martell has launched a crowdfunding campaign with GoFundMe to raise the funds.

In just nine days, she had raised $3,740 – nearly half her goal.

Since teaming up with the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers (OHCOW) on a research project in 2016, Martell said a database of 450 workers has been compiled documenting their work histories and health records. Research is ongoing to find common elements among the cases to pinpoint any links or trends.

OHCOW is additionally conducting a “first review” of cases surrounding six specific respiratory diseases: lung cancer, silicosis, sarcoidosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis and asbestosis.

“Those are ones that should, really, be granted WSIB; those are all associated with workplace exposures,” Martell said. “So we're looking at all of those cases that have not already put in a WSIB claim, or whose claim has been denied, and working to getting those claims into WSIB.”

For now, any claims associated with neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have been put on hold, as they require more research to determine any links to McIntyre Powder.

It’s disappointing for Martell, whose driving motivation for starting the McIntyre Powder Project was finding an explanation for her dad’s Parkinson’s diagnosis. But that explanation may be getting nearer.

Last year, 11 cases of ALS were discovered in the database of 450 miners, which works out to 2.4 per cent. It’s a compelling number considering the national average is two in 100,000, or 0.002 per cent, according to ALS Canada.

Similarly, OHCOW researchers have found 45 cases of Parkinson’s disease, or 10 per cent of cases, in the registry, while the Canadian average sits around 0.2 per cent.

“I honestly think that’s why OHCOW got their funding, because they can’t explain away the ALS numbers,” Martell said.