In each “Behind the Scenes” segment, Village Media's Scott Sexsmith sits down with one of our local journalists to talk about the story behind the story.

These interviews are designed to help you better understand how our community-based reporters gather the information that lands in your local news feed.

Today's spotlight is on CollingwoodToday's Jessica Owen, whose story 'On the front lines of the mental-health crisis' was published on September 7, 2023.

Here's the original story if you need to catch up:

EDITORIAL NOTE: CollingwoodToday participated in a ride-a-long with the Collingwood OPP Mental Health Response Unit on Aug. 30 and has agreed to not identify any of the clients in this story to preserve patient confidentiality. CollingwoodToday will also not identify specific locations of homeless encampments or the Busby Centre South Georgian Bay emergency shelter to protect the privacy of individuals living there.

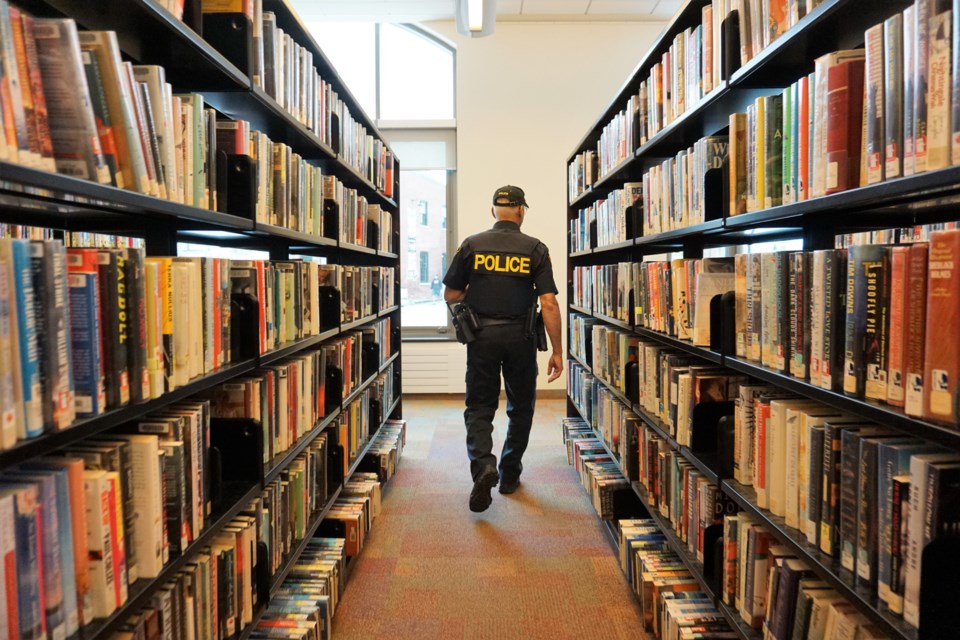

A woman in her late 20s ran toward an OPP constable and crisis worker as they arrived on the second floor of the Collingwood Public Library.

“I need to talk to you,” she said, recognizing Collingwood OPP Const. Clyde Vivian and Collingwood General and Marine Hospital (CGMH) crisis worker Amanda Kain-Johnson as people who would help her.

Through tears, the woman recounts her story. Currently living in a tent, she says all her belongings were just stolen including all her bank cards, ID, her Epi-Pen and inhaler. She says she had been recently sexually assaulted and had reported the crime to the police on Aug. 27.

The woman is wearing an oversized hooded sweatshirt that falls almost to her knees. She is not wearing pants, instead, her legs are clad in fishnet stockings, ankle socks and sneakers.

Vivian puts a hand of comfort on the woman’s shoulder while, visibly upset, she continues her story. Her sweatshirt is still damp from sleeping outside overnight.

When she’s finished, Vivian asks the woman a simple, calm question.

“How can we help you right now?” he asks, eager to assist.

This is one of many interactions the Collingwood/Blue Mountain OPP’s mental health response unit had on Aug. 30 and continues to have on a regular basis.

The unit, which was initially formed in 2016, works in partnership with the Huronia West OPP. Vivian and Kain-Johnson comprise the Collingwood/Blue Mountain team, while OPP Const. Mike Osborne and CGMH crisis worker Brittany Mauro comprise the Huronia West team. The two teams work together and will jump in to assist each other if call volumes become overwhelming.

The unit estimates there are about 90 teams using such a model in various police forces across Ontario.

A typical day for Vivian and Kain-Johnson starts by checking email to see if there were any calls from the night.

“We always seem to have outstanding follow-ups to do,” said Vivian. “Even though we weren’t designed to be an outreach program, we have moulded into that.”

On busy days, the duo will sometimes deal with back-to-back calls for service. On days with fewer calls, they might focus more on outreach and follow-ups.

“We’ll get emails from people who are, say, alcoholics. They’ll send us emails saying, ‘I need you to check on me this week.’ They know they’re getting weak,” said Vivian. “We will. It’s an open-door invitation, because it could keep them out of harm’s way.”

Kain-Johnson started out her career in psychology and occupational therapy, and proceeded to work with severe mental health cases. She came to Collingwood from Barrie in 2019 for the crisis worker job.

“I really liked people, and I really liked helping,” she said. “I love it.”

Mauro requested to join the unit after working as a nurse for years, and marked a shift for her from doing hospital-based work, to getting out into the community.

“I feel, in this role, I can make the most difference and advocate best for the clients and their needs,” she said. “We get to dig into the background and understand the situation a little bit better. I have a greater appreciation for the situations people are in.”

“I’ve found my passion in crisis work.”

Osborne was assigned to the unit in May this year, after requesting to join.

“I have some history in my family that made me gravitate towards this. I held out for this position,” he said. “I wanted to be involved with mental health because it’s on the incline. It’s so rewarding when you can actually help someone. This unit does.”

According to data provided by Collingwood OPP detachment commander Insp. Loris Licharson at a police services board meeting in July, the mental health response unit responded to 39 calls in April, May and June alone this year, and had 82 follow-ups with individuals following a call.

The unit also attended 45 outreach incidents, which is when a member of the unit will speak with an individual in distress and provide information on supports and services.

At that time, Licharson noted this equates to about a 25 per cent increase in mental health calls in 2022 compared to 2021, and another 12 to 15 per cent increase in 2023 compared to 2022.

After joining the unit, both Kain-Johnson and Osborne say they were most surprised by the call volume.

“Whatever the situation is, they’re calling the police for help,” said Kain-Johnson.

“The frequency is alarming,” said Osborne.

Vivian retired from the OPP four years ago, but was called and asked if he’d be willing to come back to participate in the mental health response unit. As he grew up in a social housing project in Toronto, he was surrounded by addiction, poverty and strife. That background led Vivian to pursue a career in policing, becoming a cadet in 1978.

“I’m proud to be a part of this collaboration. In my 30 years of policing experience, there’s never been a more satisfying position I’ve held,” said Vivian.

Both Vivian and Osborne say the relationship between them and the crisis workers is mutually beneficial, as they’ve both learned a lot about how to deal with people in crisis including science-based approaches, compassionate language and methods of deescalation from their counterparts.

“We learn a lot from these guys,” said Vivian.

Vivian says when front-line officers attend mental health calls, the apprehension rate is at about 47 per cent. However, when the mental health response unit attends calls, that number drops to between seven and 11 per cent apprehension.

“It helps the patient to get ... the treatment they need. I love that part, where we’re not apprehending so much. It takes strain off the emergency department too. It helps with so many different pieces,” said Vivian.

The unit networks with other agencies that offer other outreach programs such as the Busby Centre South Georgian Bay, Home Horizon and My Friend’s House. They will connect clients with employment agencies, job-finding agencies, health care, food services, shelter or any other service a client may need to help them along their journey toward health. They’ll also help clients apply for social assistance such as the Ontario Disability Support Program or Ontario Works.

“I do think we’re making progress, especially in this community. We know who to call,” said Kain-Johnson.

‘There have been times when calls have reduced us to tears’

Shortly after 10 a.m., Vivian and Kain-Johnson walk up Hurontario St. to check on clients that might be panhandling on the sidewalk. They stop in front of the CIBC and speak with a man in his 50s who is sitting on the ground with a cup at his feet, with some small change collected in the bottom of the cup.

The man’s face lights up with a look of familiarity when he sees Vivian and Kain-Johnson. He tells them he has pain in his knee today, but he’s otherwise OK. He says he backslid into his addiction following the death of his girlfriend from an overdose last December.

“I like sleeping downtown because it’s quiet and there’s no bugs down here,” he tells them.

He is on the social housing wait-list with the County of Simcoe, and has been bumped a few times, but he still holds out hope. Kain-Johnson says she thinks she saw him recently near the Tim Hortons cleaning up garbage.

“I’ve been doing that for years. It just takes an hour or so,” he says.

Vivian asks the man what his plans are for the winter. The man says he’s thinking of putting an ice hut out on the lake. He says he doesn’t care to stay in the Busby shelter because he’s worried about losing his belongings and they make clients leave by 7 a.m. Sleeping in a tent is also not an option he wants to consider, because it reminds him of the time he spent with his girlfriend, when they slept in tents together in encampments across Collingwood.

“If it’s ever a really cold night and you need something, please let us know,” says Vivian.

A passerby then drops some change in the man’s cup.

“These are good people. They just have things going on in their life they wish they didn’t have to deal with, but they do. We try to offer a glimmer of hope through that struggle,” Vivian told CollingwoodToday as they walked away.

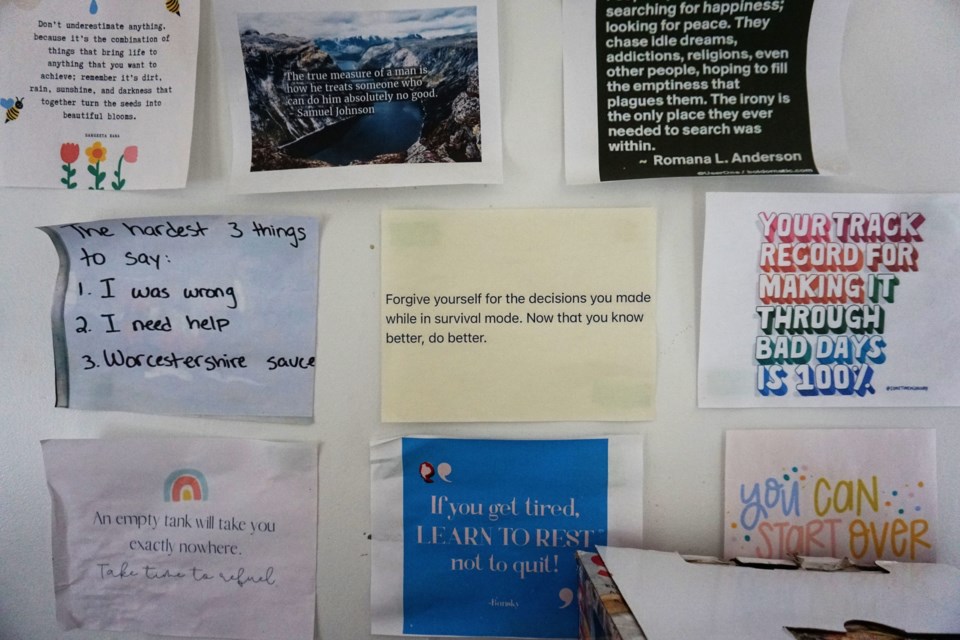

Following the interaction, Vivian and Kain-Johnson talk about how they manage their own mental health when they spend their days helping people through their own crises.

“It’s really important that whatever job you do, you take care of yourself,” said Kain-Johnson, noting that the little things such as eating well, getting good sleep and taking time away when you need it, helps.

She also says another benefit of working on a team is the ability to debrief together after a particularly stressful call.

“There are a lot of situations that are absolutely heartbreaking, frustrating and perplexing,” she said. “But, if I don’t take care of myself, I’m not going to be good at taking care of somebody else.”

Vivian says everyone processes things differently, but there have been things he’s witnessed that have made him more appreciative of the things he has in his own life.

“There have been times when calls have reduced us to tears,” he said. “You get a grip on reality and you have to be strong and move forward to get the necessary help this individual needs.”

“As much as we help them, it helps us,” said Vivian.

At about 11:15 a.m., the team’s next stop is at the Busby Centre South Georgian Bay’s emergency shelter in Collingwood’s east end.

The Busby Centre South Georgian Bay shelter offers seven beds, with two more emergency beds set aside for emergency OPP use. Busby also administers the motel voucher program, which is typically used by families. There are anywhere between 12 and 15 people on-site at all times, and the shelter typically runs full most nights.

“They are one of our biggest friends in this community,” said Vivian.

The shelter was started in 2019 and was originally called Out of the Cold Collingwood, with Busby taking over administration in the middle of the pandemic. Prior to the formation of the shelter, the only option for emergency shelter in Collingwood was the motel voucher program which was, at that time, run by the Salvation Army.

Having the emergency shelter in Collingwood has made a major difference to the work of the unit.

“It’s an option we never had before. It’s wonderful,” said Vivian.

At about 12 p.m., Vivian and Kain-Johnson stop at an encampment in Collingwood’s west end. When they pull up, a man in his 40s and a woman in her early 30s walk up to the car on their way into town, with smiles on their faces as they approach the driver’s side and Vivian rolls down the window.

The couple say the encampment is pretty wet from the rain the previous night. They’re hopeful with the hot weekend forecast that things will dry out.

“Do you need anything out here?” asks Kain-Johnson. Vivian asks how they’re doing for food.

“We could always use more tarps and blankets,” the man says. “Because of the wildlife, food is a daily thing. We don’t like to bring food in, because (animals) will whip through our shit.”

Vivian hands the couple a $10 Loblaws gift card each.

“You should grab some lunch. Everybody loves the chicken fingers,” he says, with a laugh.

The man mutters that it’s been a long time since he’s had a hot meal before thanking Vivian and heading on their way.

Further back in the encampment, there are a couple of trailers that have popped up new this year. One of the trailers is covered with camouflage netting for privacy.

Vivian and Kain-Johnson spend a few minutes talking with a man in his late 40s who oversees the encampment before heading back out onto the road. He estimates there are about 10 people living in the encampment right now. While he officially lives with his mother in Collingwood, he occasionally will spend nights in the encampment.

“I like to check in on these guys and make sure they’re OK,” the man says. “We try to take care of each other.”

“Anytime you want to come by, you’re welcome. You know that,” he says to Kain-Johnson and Vivian before heading back into the bush.

The unit then spends some time driving by areas in town where vulnerable people have been known to congregate, such at the Pine St. transit terminal, a social housing apartment building on High St. and Millennium Park.

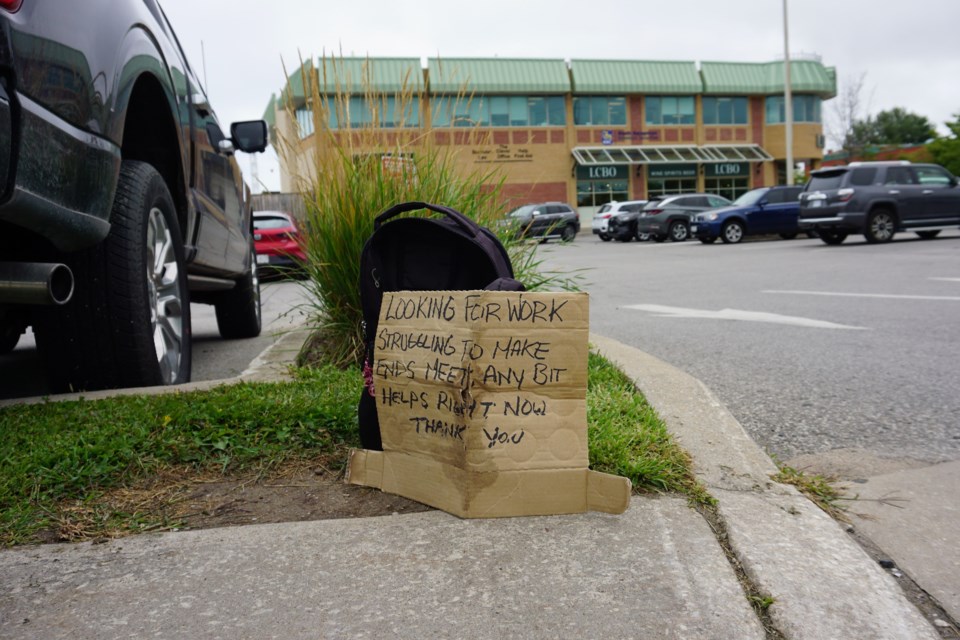

At 1:30 p.m., they come across a familiar face holding up a sign at the parking lot exit out of the LCBO.

The man in his 50s holds a sign that reads, “Looking for work. Struggling to make ends meet. Any bit helps right now. Thank you.”

The man fist-bumps with Vivian to greet him. He’s been earnestly looking for odd jobs through the sign, and says he had one person take him up on the offer and he did a day’s work for them. He and his fiancee live in an apartment in Collingwood, but they are struggling to make ends meet.

As Vivian and Kain-Johnson speak with the man, a woman in an SUV stops next to them and hands a $10 bill out her window.

“Thank you!” the man says to the woman.

“Now I’ll be able to buy dog food for Dozer,” he says.

The man’s fiancee, in her 50s, approaches with Dozer, a large but friendly rottweiler. She says she and the man have lived in a few different communities throughout their lives, and notes a major difference in how they're treated in Collingwood versus how they’ve been treated elsewhere.

“I find, out here, they’re very supportive and they want to help,” she says.

At 1:45 p.m., the team goes through a Tim Hortons drive-thru to grab a coffee each. Kain-Johnson ate a banana in the car earlier in the day, but it’s the only food the duo has throughout the shift.

At 2:30 p.m., the unit stops at the Collingwood Public Library.

Following their interaction with the woman wearing fish net stockings and an oversized sweatshirt on the second floor of the library, Vivian and Kain-Johnson spring to action. They ask her specifically what they can bring her today, and Kain-Johnson takes notes in her phone. They agree to meet her back at the library in an hour, and head back to the detachment.

Once at the detachment, Vivian goes searching for some higher-denomination Loblaws gift cards so the woman can buy her own new clothes and food, while Kain-Johnson starts going through the detachment’s community donations. She finds a new backpack, and starts loading it up with community donations of shampoo, conditioner, soap, lip balm, deodorant, a toothbrush and toothpaste.

While at the detachment, Vivian looks up the call from Aug. 27. He notes the woman declined to file a report at the detachment, and the call was one of two sexual assault calls made out of a downtown Collingwood bar that night. According to the law, in sexual assault cases, the OPP cannot charge anyone until a report is made. If the woman had wanted to get a sexual assault kit completed, the only place in Simcoe County to get one done is at Orillia Soldiers Memorial Hospital, more than an hour’s drive away. The kit also needs to be completed within 10 days of an assault.

“She isn’t in a state of mind right now to talk about next steps,” Vivian said, noting that according to the report, a friend phoned police on the woman’s behalf and the woman stated at the time she didn’t want police involvement.

“She’s probably been waiting to set eyes on us ever since,” he said.

While Vivian and Kain-Johnson are gathering supplies, another mental health call comes in over the radio for a girl under 18 years old who is dealing with a bipolar disorder episode. As Vivian and Kain-Johnson are busy at that time, the regular shift officers instead respond to that call.

After hopping back in the car, the unit heads back to the library at about 3:45 p.m.

When they arrive, they see the woman sitting in the library lobby talking with an outreach worker from Home Horizon. The woman is now wearing black jeans.

The woman is noticeably calmer than when she met with the unit earlier that afternoon. After giving her the backpack and the gift cards, they make a plan to meet again at the library the next day to see what else the unit can help her with, whether it be replacing her medications, starting the process on applying for new personal identification, getting her more food or, if she has changed her mind by then, seeing if they can help her file a report with the police about her sexual assault.

“You take care tonight,” Kain-Johnson says to the woman before she goes on her way.

A library employee then approaches Vivian about a man in his early 30s sitting in one of the chairs on the first floor of the library, who she says she thinks could use some help.

He’s new to town.

Vivian introduces himself and asks the man his name, where he came from, and if he needs anything. He explains the purpose of the unit is to help people in the community who may need some help.

The man says he moved recently to the area from Newmarket and Toronto, and wanted to get away from the bigger cities. He had plans to stay with a friend, but it fell through and he found himself staying at the Busby emergency shelter last night. He needs to call again to reserve a spot for tonight.

“I’m on methadone. That’s why I’m falling asleep,” the man tells Kain-Johnson. She asks him if he’s hungry after she gets off the phone with Busby to reserve his spot.

He says no, and once he gets to the shelter he’ll have dinner there.

“I’ll be OK,” he said.

At 4:10 p.m., 10 minutes after their shift typically ends, Vivian and Kain-Johnson get back in the car to head back to the detachment.

“We’re never done until we do as much as we possibly can to support people,” said Vivian.

Overall, Vivian says Aug. 30 was an abnormally quiet day for the unit.

“In my mind, it’s not so much about what we do. It’s about the unsung heroes like the service community people who are helping these folks through very difficult times,” said Vivian. “They’re the real champions.”

“It’s a privilege for me to be in this seat to see what’s going on in this community, and to contribute,” he said.

Kain-Johnson says she feels the same way.

“It’s a privilege to represent the hospital along with the OPP. It feels good to come to work,” she said.

Vivian says there’s been plenty of examples in his time with the unit where he’s seen people pull themselves up and out of bad situations and toward a better life.

“It’s amazing when we see the fruits of our labour... where they do have a change of circumstance backed onto the support we’ve been offering,” he said. “I’m so encouraged by it.”

“We never give up on anyone.”