GUELPH - The hospital is not empty of patients and COVID-19 is very real. Those were messages GuelphToday heard over and over from Guelph General Hospital staff during a recent tour of the Intensive Care Unit.

Staff at Guelph General Hospital have been weathering COVID-19 together for over a year now, which has led to some burnout and heartache, as well as uncertainty about what is yet to come as the third wave of the pandemic continues to progress.

Carla Schwartz has been a staff RN at GGH since 1998. She was working the day of the tour as charge nurse in the ICU.

“I love coming to work, I have loved coming here since I started,” said Schwartz. “I come to work and I put my mask on and I put my gear on and I do what I can do for the patients and I do what I can with what we have and try to give the best possible care to the patients — that they deserve.”

The last year in the ICU has been especially difficult, said Schwartz, but staff are getting through the rough patches by leaning on each other for support.

“We are coping with it okay — okay is a really broad term for me — we are coping with it fine enough," she said. "We have all been through it, it’s terrible to have to experience but we don’t have any other choice right now so we have to keep going."

But Schwartz said there are days where it all comes crashing down.

“We crumble at work and that’s okay too,” said Schwartz. “Sometimes we make it to the elevator before we cry all the way down or sometimes we make it to the car or sometimes we cry in here. Sometimes we are okay and then we watch television at home or read a book or doing something at home and see something that reminds us and we just lose it.”

Anne Hougham is part of a team of social workers that works with patients, mainly in the ICU and Emergency Department. She said all of the hospital staff lean on each other when times are tough.

“This has been a really challenging year for sure because people are not just experiencing this stress from the hospital and the sickness of patients, but their own families are impacted too in lockdowns and it’s just a lot,” said Hougham.

Like many at the hospital, her job is much different since the pandemic began in March of last year, but the core duty of supporting the patients and their families remains.

“It’s really changed during the pandemic because of families not being able to come to visit, which is necessary for safety but it’s hard on families,” said Hougham. “Sometimes it’s even finding the family and sorting out who the person’s decision maker is.”

Before the pandemic the social workers at the hospital rarely, if ever, used devices to facilitate video chats between patients and loved ones. Now it’s sometimes a daily occurrence.

“It can be quite nice because people from all over the world can do it, which can be really helpful. We have had people do prayer vigils and things like that as well,” said Hougham. “It’s touching but it’s hard, especially if there are difficult conversations that are happening by Zoom.”

Back at the nurse’s station, Schwartz said there has been times when a social worker hasn’t been immediately available.

“When the patients aren’t doing well and we have to use our own personal cell phones because social work can’t get here in time with the tablet and I am using my own personal phone as a FaceTime call for a family member to say goodbye to their family member,” said Schwartz, as her voice breaks and tears begin to well behind her eye protection. “I find that hard and I have cried and a lot of us have cried through that. It’s tough. It’s something you really shouldn’t have to do, but we’re doing it.”

Going home can sometimes add stress to the job, said Schwartz, especially when she sees people flouting public health guidelines or suggesting COVID is a hoax.

“If you are in here seeing what is happening it just gets defeating when there is constant chatter from outside saying this isn’t real or emerg is empty,” said Schwartz.

“I have to ignore all of that because that is a lot for me. They have their own opinions and I can’t change anybody’s mind, I can just change how I react to that outside noise — whether to look at it or not look at it and I choose to not acknowledge it because it gets frustrating. It eats away at us because I think I work really hard with my colleagues since March 14 of last year. That’s the last time I hugged my mom.”

Schwartz said she wouldn’t be able to forgive herself if she was the reason her parents became sick with COVID.

The ED is currently averaging about 150 people per day, said Michelle Bott, senior director for patient services at GGH. That's not far off the pre-pandemic average of 170 per day.

Although some COVID-positive patients are treated in the ED, the ones who are most sick are treated in the 27-bed ICU located two floors up. Just last week the hospital opened four new beds made possible with a boost in funding from the province.

Bott said they recently started accepting COVID-positive patients from hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area to take pressure off the system as a whole. As of midnight on Tuesday there was a total of 768 COVID patients in ICUs across the province.

“It’s becoming concerning in terms of total volumes in the province and because we are an interconnected system we are helping other areas and in turn those areas help us when we are overwhelmed,” said Bott. “I know it’s hard for people, I really do, and I know we are all kind of sick and tired of COVID but we all have to push through and take precautions as long as we can.”

The biggest difference with the current wave of the pandemic is the age of the patients coming through the ICU.

“As a society we think this is something that is impacting older people because that is what we saw — over 80 were at the highest risk — and it’s not the case anymore. We have vaccinated those patients, they are staying out of hospital so the vaccines have been quite effective,” said Bott. “Patients now are in their thirties, their forties and their fifties and they are very critically ill. We didn’t see that as much in previous waves.”

Seven COVID-positive patients were in the ICU on the day of the tour, but that number was in flux as more patients were being brought in and others were being moved from Guelph to another hospital. One patient was a parent under 40 years of age and on a ventilator.

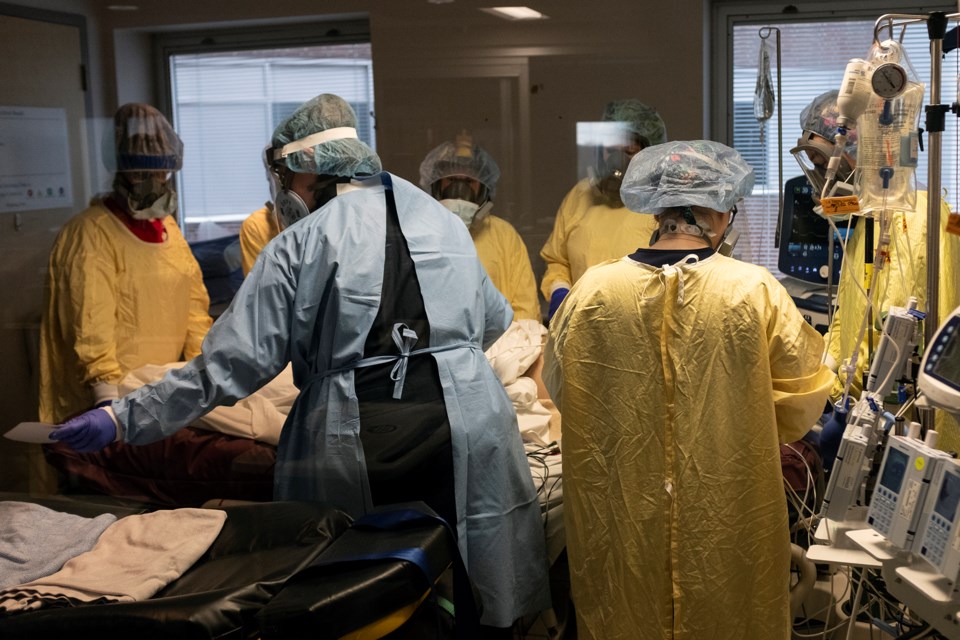

A team of six hospital staff and two paramedics took about an hour to prepare to move one patient and transfer them from the ICU ventilator to a portable one on the stretcher. It is one example of how resource-intensive the pandemic has been on the hospital, with a total of eight labour-hours required to simply move one patient to a stretcher.

Respiratory therapists like Jane Ryan-Champagne oversee intubations, a complex procedure at the best of times but especially tricky with COVID due to the risk of transmission. It involves inserting a tube in a patient’s mouth and into the airway to allow a ventilator to do the work of breathing.

“We are dealing with a lot of patients who are fighting for their lives. These are high-risk, extremely critically-ill patients, so it’s very workload intensive. It’s also physically and mentally draining,” said Ryan-Champagne. “Working with one ventilated patient uses a lot of resources in terms of staffing and equipment.”

The hospital had 10 new ventilators on order before the pandemic was called last year and soon after doubled it to 20.

Ryan-Champagne said the ventilators are treating the sickest of the sick, sometimes doing the breathing for patients for more than 20 days.

“It requires a lot from our machines. These patients are maxed-out on their settings and it takes a long time for them to respond to any changes,” said Ryan-Champagne. “Not only are you trying to keep up with the virus but their bodies are starting to shut down and you know what the probable outcome is but you keep pushing and you hope and you pray that they are going to get better.”

Ryan-Champagne said burnout among staff is a real issue.

“You have to work past it. You are not allowed to burn out,” she said.

Despite the exhaustion, Ryan-Champagne said staff are constantly offering to come in for additional shifts or finding other ways to support their coworkers, all while juggling things like childcare and homeschooling their own children.

“They are saying 'I can do six more hours here or I can come in at midnight, but I have to get up with my kids and do schoolwork,'” said Ryan-Champagne. “They are scrambling, they are struggling and they are exhausted.”

When she hears about people intentionally not following public health guidelines or claiming COVID is not real, Ryan-Champagne said she tries to not let that get in the way of doing her job.

“We are coming in and working extra hours ... then you hear or read something like that?” said Ryan-Champagne. “We put ourselves at risk every day. When you are rushing in to save someone’s life and you have to quickly put on your PPE you know you are running in and there is always a risk of breaching that and putting yourself at risk — every single time — so that can be a bit disturbing to us. It’s just unfortunate that some people believe that.”